Years ago, I was the maintenance supervisor in a biochemical plant. One day, I got called into the Operations VP’s office. He got straight to the point. “Do you want to be the maintenance manager?” I swiftly answered, “Of course.” It didn’t take long before he told me to get the budget under control. I thought, It’s only in the second month of the budget year. How bad could it be? “Well,” he said. “Your predecessor failed to budget for five full-time maintenance craftspeople, and it looks like we don’t have enough money for services. As we all know, cutting the maintenance budget is a nightmare and can end your career as manager.”

Suddenly, the budget was my No. 1 priority. It took a lot of hard work and convincing, starting with the maintenance crew. The first meeting with the maintenance staff was hard to get through and emotions were running high. Supervisors and engineers were angry and disappointed because it disrupted their work. Still, we needed more data to manage the budget, and they did get past it and agree to start gathering the data. Our quest was to assess the spending over the past few years and create an activity-based budget.

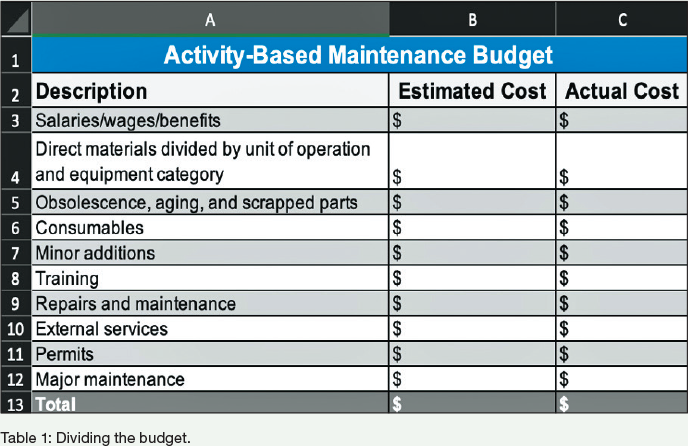

We divided the budget as shown in Table 1. With exceptional help from the planning supervisor and finance department, we managed to record the detailed spending in all categories. Now we had a great overview, with transparency on all activities and estimates of spending.

A few months later I was asked to cut the budget another 3 percent on top of the shortfall from the beginning of the year. I prepared for the meeting with the VP and headed to his office.

I showed my options for savings, and his response was, “I don’t care where you save the money—just meet the budget.”

I looked at him. “You need to agree with me about the savings so there is no finger-pointing at the end of the year.”

“I’m not interested, and it’s your job to save,” he retorted.

“Great,” I said. “Here are the activities that I will remove to meet the budget based on lowest risk and criticality for the operation.”

I ran the list:

- Replacement of ceramic valves for filtrate system

- Repair of aerators in wastewater

- Painting of structures in the older part of production

- Repairs of old VFDs for reactors

He looked up. Now he was paying attention. “That is not acceptable, and you can leave now,” he said.

I stood my ground. I would not leave until we agreed on the activities to postpone or cancel. And we finally agreed. Three activities would be postponed, and he would find money for the VFDs in the operating budget. As I left his office, I heard him mutter, “Ugh, you make this so difficult!”

Later that year, I noticed that each manager of the operating departments pushed our maintenance leads to replace parts instead of repairing them. Can you guess where the money came from? That’s right—the maintenance budget.

In my opinion, this was a waste. Why would we replace components that have years left of service without requiring major repair costs? I suggested to the VP and the management team that each operations manager should be responsible for direct material spending, together with me as the maintenance manager. They had to meet the direct materials budget. At that time, I think it really clicked that the cost effectiveness of each repair needed to be determined.

THE STRUGGLE IS REAL

We continued to struggle with prioritizing the work between areas with different stakeholders. It seemed like work and resources were assigned to those that were “barking” the loudest. Without a clear priority as to which department to help first, maintenance was left hanging in the middle.

To provide focus in all areas of the plant, we split the organization like this:

- Maintenance of production assets

- Project engineering and improvements

- Facility services

- Utility operations

As we continued to monitor the budget, we noticed that the minor additions account was a bit of a free-for-all. It was already over budget within the first six months. Operating departments were accustomed to spending maintenance dollars for minor upgrades that did not meet the capital budget requirements.

We made an agreement with the management team. Improvements and equipment changes must be approved by the department manager and the owning department must budget for minor additions before the project. That way, maintenance resources could focus on repairs and preventive maintenance. The procedures were included in our Management of Change (MOC) policy. As the saying goes, “never spend money before you have it.”

That brought us to “ballooning the budget.” We identified all major overhauls and replacements of equipment—major maintenance—in detail. In the past, major jobs were included in the maintenance budget. For example, a scheduled three-year overhaul of a two-stage 2,000 HP centrifugal compressor would cost around US$500,000-700,000. These types of major maintenance costs caused the budget to fluctuate 10-15 percent each year. We discussed this with the finance department, which wasn’t happy with activities changing so much from year to year. So, we agreed that only routine and annual maintenance would be part of the regular maintenance budget. We also created a fund that would offset the major overhauls needed to control the budget and balance cost over several years.

For all of us in management roles who have been called up to the VP suite, we know how much blood, sweat, and tears go into meeting the budget and doing a great job. At the end of the year, we met the goal for the maintenance budget. It was hard, I spent many long days and nights making it work, and we learned a lot as a team. Two of the most important lessons were: 1: If you have a detailed-activity or zero-based budget, you know exactly where the money goes; and 2: You shouldn’t agree to lower the budget unless you have support or agree with your manager and the management team about which activities will be canceled or postponed.

Cutting the maintenance budget will never be a walk in the park, but it will be easier if you have a plan that is well thought through and a partnership with the plant management team.

Paper 360

Paper 360