CHRISTER IDHAMMAR

IDCON FOUNDER, RELIABILITY AND MAINTENANCE GURU

Gemba (US gem.b ) noun. In Japanese business theory, the place where things happen in manufacturing. Used to indicate that people making products are in a good place to improve the process by which they are made.

Mills exploring the gemba approach need to decide which positions will take responsibility for “doing the gemba walk.” For gemba positions to be effective, the managers above them must set up the processes. These processes should be documented, communicated, instilled, and frequently followed up on. People are enabled so they actually can and will follow the process they are required to work in.

Gemba walks are a tool to learn how well the processes are executed and what you need to do to improve them. They are only effective if you are actually walking the floor to observe and learn.

During my six decades in the industrial RMM field I have frequently experienced how the gemba of RMM has been ignored or not given enough support. You may be wondering: “Christer, who are the gemba people or positions in RMM?” That’s a good question; let’s look at the frontline positions or functions in RMM:

1. Crafts people and operators who execute the work;

2. Frontline leaders/supervisors who schedule, support, and lead work;

3. Planners who plan work;

4. Coordinators who filter, prioritize, and coordinate work between Operations and Maintenance;

5. Reliability engineers who facilitate Root Cause Problem Elimination (RCPE) events and implement the preventive maintenance program including lubrication, basic inspections, predictive maintenance and justified fixed time replacements and rebuilds.

In a smaller maintenance organization, there might not be a person filling each of these roles or functions, whereas bigger organizations may fill each position.

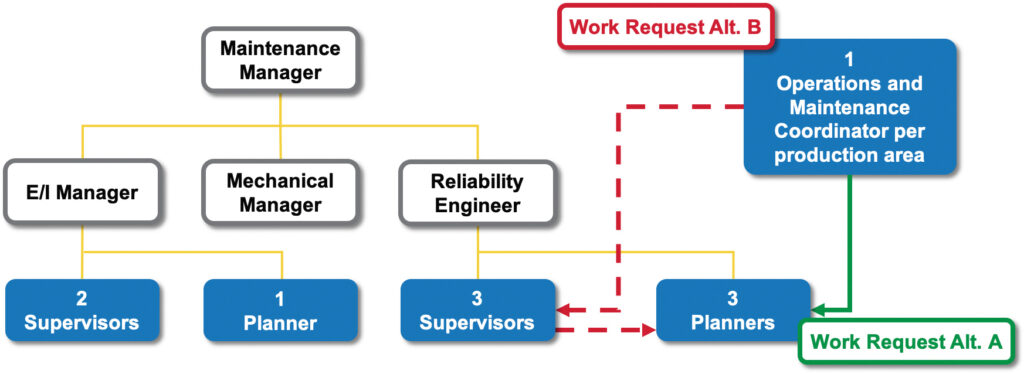

Figure 1 depicts a well-resourced maintenance organization. This organization has 15 E/I technicians and 33 mechanical crafts people. The blue boxes represent the maintenance frontline. In this example, each operations and maintenance coordinator (OMC) receives, validates (filters), and completes each work request from their respective area.

Note how all filtered work requests are sent to the planner for that area, who will plan work for scheduling according to requested priority (Work Request Alt A). In the alternative B, work requests are sent to supervisors for a second screening and to plan repetitive work with existing job plans. In this scenario, planners will then have more time to focus on bigger jobs and planning shutdown work.

Of course, your organization may have a different setup and your work processes should be designed to fit your unique setup. It is important to continuously follow up and encourage that the system works as intended and delivers expected results in safety, equipment reliability, and costs (in that order).

At this point, I will ask readers to pause and assess for themselves: When was the last time we reviewed our workflows? Do they still match our current organizational setup?

Maintenance managers, some goals you should have are to be visible, engaged, and aware of barriers that hinder the frontline from doing a safe and productive job. Regular gemba walks are a good tool for you to accomplish these goals.

HOW TO GEMBA WALK

A gemba walk isn’t an ambush. Let team members know you’re going to observe and engage them with questions. They should understand what a gemba walk is and how it’s going to be useful to them. Talking about the gemba walk, and the outcomes, will put them at ease and help them stay open to the process.

Prepare your questions before you visit each frontline person. Ask open questions. A good way is to start is with “Tell me” as this will engage the person you talk with from the start. Here are some examples:

“Tell me:

• …who decides priorities and work and how well that is done.”

• …more about how the use of priorities can be improved.”

• …how early you can freeze a daily schedule.”

• …more about why you have frequent schedule changes.”

• …what a typical day looks like for you.”

•…what you would like to spend more time on and what you would like to spend less time on.”

These are only some few examples of conversations you might have with a frontline person involved in the work management process.

During the gemba walk you should also look in detail at equipment. It’s good to do this before any discussions with frontline people. Examples of what to look for include:

• Alignment practices. Are there beat marks on motor feet? Are more than three shims used? Does important equipment have jacking bolts installed? Are they backed off from motor feet?

• Are safety guards made so couplings, belt and chain drives, or other components can be inspected?

• Is lighting enough and all working?

• Are the area and equipment clean? Do you see parts or tools left behind after work is done?

• Are oil levels correct?

• Are there visible leaks?

• How old are the parts in the kitted staging areas?

• Do you find spare parts and material that should be in stores kept in areas?

• Are equipment identifications visible?

• Are lubrication stores and lube tools well-organized and clean?

• What filtration standards are used for hydraulics and lubricants?

• Are washers under foundation bolts corroded?

• What is the outgoing temperature of cooled hydraulic fluids and what is the position of the control valve?

• Is rotating equipment in stores positioned so it can easily be rotated regularly?

• Is standby equipment, such as pumps, shifted to operate equal time?

Of course, this is only a partial list, but it can serve as an example. What you observe during a physical gemba walk can reveal many good examples, but also a lot of improvement opportunities. During your gemba talks you will often find solutions to many improvement opportunities. Your visible engagement as a leader will be very well received and you will be in a much better position to lead your organization to success.

TAKING THE TIME

You might feel you do not have time, but I think most maintenance managers can free up less than half a day once a quarter per maintenance area to do this. Each time you do it you should focus on one subject—for example, work requests and prioritization for one walk, preventive maintenance next time, etc. In bigger organizations you can delegate some of these walks to your closest reports.

To successfully and sustainably implement an improvement initiative takes time because it is 90 percent about people, culture, and behaviors. Here’s how that time typically breaks down:

• to develop the implementation plan should not take more than 5 percent of the total time;

• to communicate the plan—telling the why, what, and how—and train people should take no less than 10 percent of the total time; and

• the remaining time is to coach and do on-the-job-training with the RMM gemba people.

Often, I see “Happy Islands” of people developing the improvement plan, but spending way too little time communicating and coaching the actual implementation and continuous improvement. Improvement initiatives that fall in this category are bound to fail because the only result is a plan, but no execution.

Paper 360

Paper 360