MARKO SUMMANEN, FISHER INTERNATIONAL

In general, specialty paper producers are small—often smaller than their suppliers or even their customers. Most specialty paper products are made with small and old machines. Average deliveries are small and some grades can be vulnerable to competition from larger machines that have been converted from other grades, such as newsprint or printing and writing. Customer service and logistics acumen can protect small specialty paper producers; nevertheless, some specialty products are already being made with bigger machines, begging the question: Will there be further shifts toward bigger machines in the future?

Specialty paper producers face many challenges, but they also have numerous opportunities as technology is changing rapidly and new products are being developed that will enjoy market growth in the long term. Urbanization and aging populations are trends that will create new opportunities for specialty producers. New products such as individual packaging for food that can be refrigerated, heated in the oven, and served to the end-customer in a one-and-the-same container create more value for producers capable of making such paper products. New medical products, together with the need for clean water and air, offer new avenues of opportunities as well.

Specialty paper producers face many challenges, but they also have numerous opportunities as technology is changing rapidly and new products are being developed that will enjoy market growth in the long term. Urbanization and aging populations are trends that will create new opportunities for specialty producers. New products such as individual packaging for food that can be refrigerated, heated in the oven, and served to the end-customer in a one-and-the-same container create more value for producers capable of making such paper products. New medical products, together with the need for clean water and air, offer new avenues of opportunities as well.

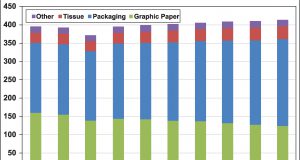

Globally, and compared to other paper grades, specialty grades are growing—albeit not at the rates seen in packaging and tissue (Fig. 1).

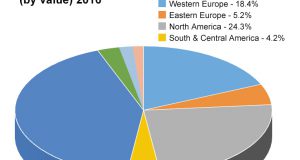

In Asia (notably China), specialty paper is growing rapidly while Europe and North America have seen declines, though this has recently flattened out. Globally, specialty grades like art paper, laminating, packaging and even cigarette paper are growing, while communications and wall lining are trending down (Fig. 2).

Historically, we can say that Europe dominated in adding specialty paper capacity until the late 1980s and then Asia took over, becoming the main growth driver ever since. Overcapacity is inevitable, partly because of repurposing. Despite this, a lot of the machines are still small, even in Asia, which is to be expected given the low-volume demand for many highly specialized grades.

FIBER DEMAND

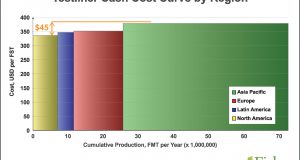

Most specialty mills are either non-integrated or use recycled fiber. Consequently, fiber raw materials represent more than 50 percent of all their cash costs, with kraft pulp being the biggest furnish component in all regions. Fiber thus presents a huge risk variable to specialty producers (Fig. 3). While for most major grades, about half of the chemical pulp needed for furnish is integrated, for specialty papers, integrated pulp is a very small part of the total furnish—maxing at 20 percent, except in North and Latin America, where it is significantly higher.

In the next five years, demand for chemical pulp (integrated and market) from printing and writing grades is expected to decline by close to one million tons, according to Fisher’s models. At the same time, specialties will increase demand for chemical pulp by about 800,000 tons.

Meanwhile, Brazil’s announced new hardwood kraft pulp capacity is likely to exceed global demand. Given the low-marginal cost of production in Brazil, Fisher estimates that, if prices fall due to oversupply, 5-6 million tons of

Chinese pulp production may be at risk, as the Chinese government pressures polluting and inefficient producers to close down.

Chinese pulp production may be at risk, as the Chinese government pressures polluting and inefficient producers to close down.

Access to low-cost fiber will be a focal consideration for entering the specialty paper business—but new technology and scale are important, too. Most specialty producers today are relatively small when compared to their suppliers and customers. What if a large specialty customer decides to start its own production of paper? Or if large customers consolidate, making them big enough to justify the addition of larger new machines? Location and logistics are also clearly important, as are low-cost energy, vertical integration to the end product chain, knowhow, and good customer service.

As packaging producers are demonstrating, downstream integration is a means for improving profitability and serving end-users in new and better ways. This is so important that the paper producing part of the equation is becoming a less dominating driver of some packaging producers’ businesses. Can this be the model for some specialty producers as well?

In specialty grades, cash cost profiles are very steep (Fig. 4). This makes it fairly safe to invest in the first quartile of the cost curve for any given specialty grade. Globally, almost 25 percent of current specialty assets are at high risk, mainly because they are small, old, and high-cost.

SPECIALTY PAPERS IN

GLOBAL TRADE

It is surprising how little apparent global trade there is in some specialty grades. Already low freight costs are shrinking around the globe, so it could be cheaper to ship to the US East Coast from Portugal than from Minnesota. The impact of this new “Silk Road” is unknown, but it could encourage new international trade flows. Approximately 35 percent of NBSK market pulp is traded, compared to less than five percent of grease-resistant and filter papers (Fig. 5). That may change as transportation costs dive and customer size increases. Global trade is no longer just for big commodities.

For specialty producers able to sell globally, there are plenty of opportunities for export. Let’s take Europe as a case in point. The decline of the Euro is helping Europe increase exports to the US and to build new export-oriented capacity. Among others, Gruvön, Husum, and Varkaus have all rebuilt machines and are exporting to the US. There is, for example, no parchment production in the US, though the percentage growth rate is high, so Europe can

export to this market and investment in this grade is very safe.

export to this market and investment in this grade is very safe.

Worldwide, there are 588 mills selling about 22 million tons of specialty paper listed in the FisherSolve database. In Europe, there are currently 165 sites with 278 machines making newsprint and printing and writing paper, 49 of which also produce specialty papers (Fig. 6). This amounts to nearly one million tons of Europe’s specialty paper being made on machines producing newsprint and printing and writing grades. Most of the printing and writing machines are small, old, and not efficient, but they could be converted into specialty machines.

Most of the lines making specialty papers in Europe are privately owned (62 percent of capacity) with all that that implies for continued operation under difficult conditions, and for intense competition (Fig. 7). Most of the small machines making printing and writing, newsprint, and packaging are also privately owned and are more likely than those in public companies to be repurposed.

There are more than 50 machines in Europe making printing and writing paper that are only 2.5 meters wide; these are a prime target for conversion to specialty papers (Fig. 8). Particularly, we can expect machines making woodfree papers in integrated chemical pulp sites to be candidates for conversion.

Marko Summanen is VP business development for Fisher International, a consulting firm that supports the global pulp and paper industry with business intelligence and data-driven strategy consulting. The information and analyses for this article are drawn from FisherSolve™, the industry’s premier market intelligence database and analytics resource. To learn more, please visit www.fisheri.com. Marko Summanen can be reached at

[email protected].

Paper 360

Paper 360