trendspotting | MANAGEMENT

An Ode to Small

A bold management decision in 2013 has revitalized Turners Falls Paper.

GRAEME RODDEN

Find a niche

Find a niche, be the best at what you do, serve your customers like no others, be quick to respond to evolving markets. How does a small papermaker survive, and thrive, in this era of declining demand—especially when one’ s assets date back to the 1930s?

Privately-owned Turners Falls Paper, Turners Falls, MA, traces its company history back to 1839, although the mill, originally known as the Esleeck Manufacturing Company, was built in 1898. (See sidebar.)

As with most mills of that era, its main raw material was cotton rags used to produce a very lightweight paper (e.g., onion skin), according to present-day Director of Technology and Innovation Ken Schelling. The original rag boilers are still in the mill and were used up until 2002-03. The mill now buys processed rag fiber and, depending on the paper grade, makes up to 100 percent of the furnish.

In the early 1900s the mill was one of the largest producers of paper for a new technological marvel, the typewriter. The mill continued as a lightweight paper producer and also went into new grades. However, over time markets declined, and by the beginning of the 21st century the mill was running only three or four days a week. An older management team was not thinking of new markets and it seemed like the mill’ s days were numbered.

A GIANT LEAP INTO THE UNKNOWN

In 2006, the Southworth family acquired Esleeck Paper and the Turners Falls mill. Until recently, the mill was known as Paperlogic, but in 2016 it was renamed Turners Falls Paper. The research division, formed in 2013, still uses the Paperlogic name.

Although the Southworth family still owns the mill, it made an extraordinary decision in 2013 when it sold the Southworth line of papers (P&W) to Neenah. The line represented 50 percent of production.

“ This was a brave thing to do,” admits Schelling, who has been with the company since 2009. “ What we do today is rep-resentative of what we had to do when we sold the Southworth line.”

Although the market was shrinking, the decision to sell was made quickly. As a result, there was no infrastructure in place to make new grades or sell them. Management’ s decision was to concentrate on the colored paper market—artists’ grades. (The mill had started making colored paper after Southworth acquired it in 2006.) This would complement the businesses that were kept, such as envelopes, archival paper, and other specialty paper, some with a cotton rag furnish. The mill still is considered a preeminent producer of cotton fiber papers.

The bold change in production has paid off. According to the Turners Falls Paper website, “ Colors are a common occurrence in our manufacturing schedule, often for several days in a row.”

And, although there are several long-term customers for products such as vellum, Schelling estimates that 30 to 40 per-cent of the business comes from customers of fewer than five years’ standing. He says, “ Turners Falls Paper is a custom paper manufacturer. Most of production is made to order. The only real line we have is the Byron Weston brand.”

There is an everyday reminder to operators and staff of the peril of an unwillingness to change. Adjacent to Turners Falls is another old mill, originally Keith Paper, which went through various owners (Strathmore-Hammermill-IP) through the years before being shut for good in the late 1990s. The two mills built one of the first effluent treatment plants on the Connecticut River. Turners Falls still uses it today.

THE ORDINARY CAN DO THE EXTRAORDINARY

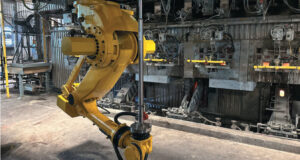

Schelling explains that there is nothing extraordinary about the mill equipment. Having come to Turners Falls after working with a supplier, he says the most “ remarkable thing is that nothing about the machine is unique.”

But this simplicity provides benefits, one of which is flexibility. “ One of the benefits of an older machine is that it can pro-duce a wide range of basis weights.”

The flexibility also allows experimentation with new technology and various fiber treatments. The company considers it a welcome challenge to try something new. The machine, a Rice Barton unit (110 in. maximum trim) installed in 1939, features a Manchester Machine headbox. A sign of the times from that era: most of the papermaking machinery was built locally.

Over the years the machine has gone through various rebuilds/updates. It still has table rolls and a conventional twin nip press. Originally, the sizing and supercalendering were done offline, but by extending the machine room, a Hunt & Moscrop size press and soft nip calender stack were installed online. A modern Chroma Logic color control system has helped op-timize dye use and color matching. Centrifugal cleaners have also been added.

For the extensive range of papers it produces, proper stock prep is critical. Making it more complicated are the various raw materials the mill purchases: conventional hardwood and softwood pulp, and cotton rags and linters. Turners Falls also makes grades with bamboo fiber and is looking at wheat, hemp, jute, and banana fiber.

“ With all the grades we make and the fiber we use, we need to concentrate on fiber preparation—for example, refiner plate design. Are we optimizing the properties of the fiber we have?” Schelling explains.

The stock prep room has two washers (although only one is needed at a time), a breaker (for cotton rag), and two Bertram beaters. There are DD refiners, although one is dedicated to the production of cellulose nanofibers (CNF), part of the mill’ s research group.

As a custom papermaker, Turners Falls must adapt to numerous grade and color changes daily. It specializes in small runs, as low as 3,000 lbs; for example, a facing paper run is usually 3,000-5,000 lbs, and takes about two hours of machine time. Basis weights range from 40 to 550 g/m2.

As Schelling says, the biggest challenge with small runs is minimizing unsalable paper and maximizing machine uptime; “ On a good change, we can be on spec in 20 minutes.” On average, there are six to eight changes daily, although Schelling has seen as many as 11.

The mill’ s operators’ experience helps. “ We set up runs to minimize dramatic changes,” Schelling adds. For example, in one day in March 2017, the machine went from making blue paper to red to pumpkin to gold.

The critical objective is to set the desired color in the pulper—that is, doing the color match work ahead of the paper machine. “ We don’ t want to ‘ chase’ the color in the wet end,” Schelling says. “ Otherwise, you can change the wet end chemistry.”

Along with the colored paper, Turners Falls makes a wide range of papers, as can be seen by the basis weight range: artist paper, vellum, museum boards, Bristol, vellum sheets (there is an offline Maxson sheeter), watermarked paper, and enve-lope (this is converted at an off-site facility).

Annual tonnage depends on basis weight. “ Our niche is smaller runs, 3,000-5,000 lbs,” Schelling adds. The ability to change rapidly and produce such a diversity of grades came about because “ We were able to define the capabilities of the paper machine.”

Although the sheeter is available, about 70-80 percent of production is shipped as rolls. Employment at the mill numbers about 60, with a good mix of experience and youth, according to Schelling. Finding em-ployees can be a challenge, as unemployment in the area is low.

RESEARCH HAS AN IMPORTANT ROLE

Unlike most of its colleagues in the industry, Turners Falls has kept its research arm. How can such a small company afford to do so? In a word: desire. “ It is a challenge,” Schelling admits. “ We have a small staff and everybody contributes. A lot of re-search is done in response to client requests. If we believe there is a market, we will try it. We have the desire. In fact, this is what we have most of, the desire to do it if we think we can.”

Schelling cites the 46 pt heavy weight board the mill started to make as an example. At first it was not thought possible be-cause of the age and size of the paper machine.

The Paperlogic research division has made strides in the field of CNF. “ When David Southworth sold the Southworth brand, we spoke with university researchers to see where possible paths could lead,” Schelling explains. “ One of the things we spoke of was a university using our machine for trials. One of the trials was on CNF, and we saw some nice results.”

Seeing the potential, mill management—working with the University of Maine and supplier GL&V—submitted a proposal to the US government for a grant to build a scaled-up system of the trial. It was approved. Now, as Schelling says, the question was: “ How do we use the material in paper? It gives a lot of good properties: smoothness, strength, density.

“ We work with all who call: concrete, paint, coatings, adhesives,” Schelling continues. “ One of the new grades we are stud-ying is decorate laminate with CNF in it. There are improvements in scratch resistance and gloss.”

The agricultural industry has shown interest in CNF as a seed cover. It helps hydrate the seed. “ The ideas are endless,” Schelling adds. Another agricultural application was the manufacture of a paper-based sheet that would cover fields to control weeds and improve seed germination. However, the product is not yet competitive with the conventional black plastic sheets used. This new product is also biodegradable, and Schelling says that controlling the biodegradability is the key. Work is ongoing.

In baking, CNF provides good release properties and the paper does not need to be coated. However, the product still needs US FDA approval. In other product development, vulcanizing trials have gone well. It is fiber that is vulcanized. The fiber chemistry makes them meld together like a plastic; it emerges like a circuit board. There is potential for electronic applications.

Turners Falls is also into label papers. In new furnishes, there are trials using hops in the pulp furnish. This would be a natural for brewers. The mill is also talking with people in Massachusetts as it is a medical marijuana state. Could the plant waste be part of a furnish in packaging?

Turners Falls expends a lot of effort to meet a need, whether in addressing an existing one or producing a new product. “ We push ourselves, every day,” Schelling states. “ If you look at the (shuttered) mill next door, you know what your fate is if you don’ t put in your best effort.”

He adds that the mill likes driving new technology and, in a traditionally conservative industry, that can be difficult. “ We are not afraid to fail. We can learn from failure and apply that knowledge.”

Schelling says Turners Falls tries to be “ visible about who we are and what we do. It is exciting and it is challenging. We look at anything if it makes sense. We do have a lot of flexibility and latitude to try new things.”

Graeme Rodden is senior editor, North and South America, Paper360°, and can be reached at: [email protected].

A Glimpse of a Bygone Era

The history of Turners Falls Paper is a fascinating web of interlocked stories that traces the early roots of the American paper industry in Massachusetts.

In 1839, Wells Southworth founded a fine paper mill in West Springfield, MA. It operated until a fire in 1870, then was rebuilt and run until 2006 when Esleeck Paper was acquired. Operations were then transferred to Turners Falls and the mill was shut.

Elsewhere, in the 1860s Byron Weston founded Weston Paper in Dalton, MA.

Weston himself had worked on one of the first fourdrinier paper machines in New York and then at Smith Paper before building his own mill. The Weston line is still produced, now made by Turners Falls after it purchased the line from Crane in 2007-08. Weston produced security and currency paper and made the first social security cards in the US. To this day, as one Turners Falls sales representative says, if you were born in the US, bought land, married, died, or served in the military, somewhere along the line, you would have a paper trail from Byron Weston.

In 1898, the Marshall Paper Co. mill was built in Turners Falls. For some reason, it never made paper and in 1901 it was purchased by the Esleeck family and started production as the Esleeck Manufacturing Co.

Turners Falls itself was a hotbed of industry in the late 18th century. Among the businesses in the area were RussellCutlery; Montague Paper; the original Turners Falls Paper mill, which burned in the 1950s; and a textile mill.

The 20th century ushered in the era of acquisition. First came the Weston assets. Then, in 1996 Eaton Paper was ac-quired. Eaton was a papermaker with mills in western Massachusetts. Finally, Esleeck Manufacturing was acquired in 2006. Today, it is the only mill of all the aforementioned still operating.

The Southworth family still controls the mill. Family member John Leness is president and works from the Pacific Northwest. The management team at the mill consists of David Mika, CFO and treasurer; Rob Binnall, vice president, sales and marketing; and Ken Schelling.

Find a niche, be the best at what you do, serve your customers like no others, be quick to respond to evolving markets. How does a small papermaker survive, and thrive, in this era of declining demand—especially when one’ s assets date back to the 1930s?

Find a niche, be the best at what you do, serve your customers like no others, be quick to respond to evolving markets. How does a small papermaker survive, and thrive, in this era of declining demand—especially when one’ s assets date back to the 1930s?

“ With all the grades we make and the fiber we use, we need to concentrate on fiber preparation—for example, refiner plate design. Are we optimizing the properties of the fiber we have?” Schelling explains.

“ With all the grades we make and the fiber we use, we need to concentrate on fiber preparation—for example, refiner plate design. Are we optimizing the properties of the fiber we have?” Schelling explains. Unlike most of its colleagues in the industry, Turners Falls has kept its research arm. How can such a small company afford to do so? In a word: desire. “ It is a challenge,” Schelling admits. “ We have a small staff and everybody contributes. A lot of re-search is done in response to client requests. If we believe there is a market, we will try it. We have the desire. In fact, this is what we have most of, the desire to do it if we think we can.”

Unlike most of its colleagues in the industry, Turners Falls has kept its research arm. How can such a small company afford to do so? In a word: desire. “ It is a challenge,” Schelling admits. “ We have a small staff and everybody contributes. A lot of re-search is done in response to client requests. If we believe there is a market, we will try it. We have the desire. In fact, this is what we have most of, the desire to do it if we think we can.” Turners Falls expends a lot of effort to meet a need, whether in addressing an existing one or producing a new product. “ We push ourselves, every day,” Schelling states. “ If you look at the (shuttered) mill next door, you know what your fate is if you don’ t put in your best effort.”

Turners Falls expends a lot of effort to meet a need, whether in addressing an existing one or producing a new product. “ We push ourselves, every day,” Schelling states. “ If you look at the (shuttered) mill next door, you know what your fate is if you don’ t put in your best effort.” Paper 360

Paper 360