This is the third installment in a year-long series by corrugated equipment specialist Jim Brown. Articles will outline what the board experiences during the conversion process, but from an unusual perspective: that of the board itself, in the form of our imaginary narrator, Corra Gator-Boardy.

Ride along with Corra in a series of six mini-adventures on her way from a flat corrugated board to an amazing, corrugated container.

When we last saw Corra, she was emerging proudly from the three print units that had applied her colors. She was cruising comfortably through a transitional vacuum transfer area, drying as she went.

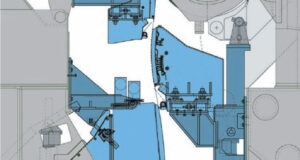

Yet ahead of her she could hear an awful chomping sound, like jaws tearing through corrugated. Suddenly, there it was in front of her, full machine width across. It was a rotating cutting die with sharp knives that were cutting into thick, urethane covers on the lower anvil drum. There was no way forward except through!

Corra closed her eyes and held her breath as the knives cut hand-holds and air holes cleanly through her. Like a rotary cookie cutter, the shapes were quickly separated from the board.

As she passed through, the scrap pieces inside of the knife shapes were ejected by rubber that had been compressed during the cut. She was taking shape, gaining meaningful features as she went. Looking back, she could see the shiny knives rotating on the upper die drum, and the dull, urethane anvil drum covers that were taking the brunt of the cutting action.

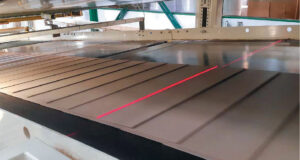

Corra was curious how the surface of the anvil covers remained so smooth and consistent in thickness after repeated cuts and pounding by the upper die. That’s when she looked down and saw the anvil grinder, with a full-width, gold-colored, spinning roll that had sharp, tungsten carbide bits attached to its surface. It was like rotary sandpaper. It was mounted on slides and would advance toward the anvil covers, take a .001″ grind every 10,000 sheets and then retract, all under the cover of the scrap shield.

How awesome, she thought. The servomotor must know the exact position of the grinder roll, which could measure the anvil cover outer diameter. That means as it got slightly smaller from grinding, the machine could compensate by spinning the anvil drum slightly faster! That was accomplished by a servo-controlled, variable speed upper pulley. It could add to or subtract from the rotational rpm of the drum to get it just right.

So, in real time, with no intervention from the operator, the anvil grinder system could keep the linear board speed (i.e., the surface speed on the anvil cover surface) constant, regardless of the diameter of the anvil covers, until their minimum thickness service limit was finally reached.

But wait, Corra thought…don’t the cutouts in my panels also need to be in the correct position? She knew the answer was yes, because she saw an identical registration unit on the upper die drum as she had seen on the print cylinders. In the exact same way, the registration of the die cuts could be adjusted into spec, both laterally and rotationally, with respect to the edge of the sheet.

Corra had one final thought as she left the die cut section: Where did the scrap from her cutouts go? She saw them being ejected from the knives on the cutting die and fall onto the scrap shield, sliding to the bottom and onto a side scrap conveyor. The conveyor transported the scrap on a flexible belt to the drive side of the machine. As the small scraps fell off the pulley, they were sucked up a vacuum hood and transported to the roof through a centralized dust and scrap collector system.

This is great, but where would she be going next? How would she become a real box that could stand up on her own? Stay tuned as Corra nears the end of her conversion in Part 4, appearing in the Paper360° July/August issue.

Paper 360

Paper 360