It would appear obvious that reliable operation of our production equipment and the safety of our plant personnel go hand in hand. When the plant is operating efficiently, we assume that the risk of hazard exposure should be reduced.

This two-part article addresses these assumptions and the important role reliability can play in safety. This month, I will spotlight the link between the safety risks of our personnel and risks associated with equipment reliability. In Part 2, I will explore how we can leverage reliability improvements to reduce overall risk, and perhaps provide some new considerations for how to apply risk reduction techniques from the world of personnel safety to enhance equipment reliability and vice versa.

WHAT’S YOUR EMERGENCY?

I think we can all agree that most severe injuries to maintenance personnel occur when “emergency” maintenance work (which is typically unplanned and unscheduled) is being conducted, as opposed to more routine work such as preventive maintenance. Can we also agree that the interaction between human and machine, and the resulting risk of injury, increases as equipment performance declines? Also consider this statement: “People are invariably fallible, i.e., they are going to make mistakes, and we need to ensure that when these mistakes occur, the severity of the resulting incident is mitigated as much as possible.”

According to a 2015 study conducted by the University of Tennessee Reliability and Maintenance Center (UT-RMC), workers at the companies that are performing the highest percentage of reactive (unplanned and unscheduled) work suffer recordable injuries at rates four times higher than companies in the middle of the pack and 40 times higher than companies that minimize reactive maintenance work (Fig. 1). These “Top 25” companies reduce reactive maintenance work through both effective planning and scheduling and effective Preventive Maintenance/Essential Care and Condition Monitoring.

Why is the risk of injury so much higher under reactive maintenance circumstances? Stress, uncertainty, fatigue, time pressures, trying to do the work with the wrong tools, failure to identify the job risks before commencing work — these are all possible contributing factors to the increased number of recordable injuries being experienced.

Managers are often guilty of assuming that work execution will be error-free if we properly prepare our workers to execute their work safely and efficiently through proper planning and scheduling of the work and proper safety training and instruction. By this logic, if an employee then gets hurt, it is their fault for getting injured. But the reality is that, as long as human beings are involved, errors are inevitable. Workers don’t go into a job thinking that whatever injury is about to occur would ever happen to them. The companies that have the most success in this area embrace human error, learn from incidents that occur, and look to build a safer workplace where people can fail safely (when they inevitably fail).

There is an entire field of study in the personnel safety arena dedicated to these types of issues. It is called Human and Organizational Performance (HOP). It is based on the overriding belief that systems drive behavior. The primary tenets of HOP are:

- Error is normal. People make mistakes. Expecting perfection is illogical and unrealistic.

- Blame fixes nothing. If you don’t correct the underlying causes, the failure is doomed to recur because…

- Systems drive behavior. Workers don’t cause failure; workers trigger failure latent in their work system. Prior to this interaction, this failure (exposure) is undiscovered and just lying in wait.

- Learning from incidents is vital. While human failure is normal, the risk of system failures can be reduced significantly through effective Root Cause Analysis and Problem Elimination.

- Response matters. The way management responds to an incident is key to establishing an effective work culture. Does your response promote learning by focusing first on the condition of the injured parties and/or equipment condition, then on the circumstances surrounding the incident and the potential for this incident to recur? Or does your response cause vital information to be ignored, instead focusing on who to blame and who should be disciplined?

There is significant overlap in industry’s focus on reliability and safety. Consider the automobile industry. Think about the improvements that have been made in reliability and safety in the last 50 years. Have we been able to eliminate all vehicular accidents given all of the technological improvements made in that industry over that time? No, vehicular accidents still occur. There were roughly 39,000 crashes in the US in 1975 resulting in 44,000 fatalities, while in 2019, there were 33,000 crashes that resulted in 36,000 casualties.

Granted, the numbers of vehicles on the roads and the number of miles driven have increased significantly in that time frame, so the fatality rates per mile driven have dropped. But the point is, accidents are going to occur. So, the automobile industry has adopted the motto “We can’t change the driver, but we can change everything else…” Think about all the technological improvements designed around permitting the driver to fail safely:

- Airbags

- Seatbelts

- Anti-lock braking systems

- Lane departure warning systems

- Crumple zones

- Shatter-proof safety glass

- Rumble strips

These are only a few. These systems are designed to acknowledge that drivers will inevitably fail, then allow them to correct their behavior before an accident happens (or increase the likelihood of survival if an accident should occur). By focusing on the inevitability of human failure by our plant personnel, we can implement systems that will alert them that their performance is operating outside of desired parameters, which should give them an opportunity to correct that behavior before incidents occur — just as we should implement systems that will alert them that the production equipment is operating outside of acceptable parameters and that action should be taken before an incident (breakdown) occurs.

We should also look to implement systems that will allow the equipment or personnel to reach a safe state before catastrophic failure occurs when their performance is falling outside of acceptable parameters. Think of a pressure relief valve on a tank that vents pressure to the atmosphere before the tank overpressurizes and potentially explodes. Or consider a portable grinder that has a mechanical clutch and an automatic brake to reduce the risk of serious injury, not if, but when, your employee accidentally exposes a part of their body to a grinding wheel rotating at 4,000 to 16,000 rpms.

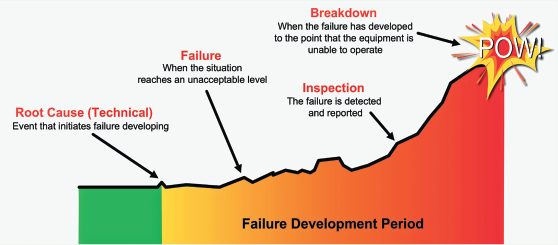

On the equipment side of things, we talk about the Failure Developing Period (Fig. 2). An event occurs that will result in a component’s performance to leave acceptable operating parameters. We will call this the Root Cause. Once that event occurs, as performance has begun to degrade outside of acceptable parameters, failure is deemed to have occurred.

Eventually, the condition of the component will continue to degrade until it reaches the point where it cannot continue to operate. We call this the breakdown. The period between the occurrence of the triggering event and the breakdown is called the Failure Developing Period.

Good maintenance practices should include inspection of the condition of this failing component at a high enough frequency (for instance, twice during the Failure Developing Period) to allow for a planned and scheduled corrective action to be taken to repair or replace this failing component before breakdown occurs.

SAFETY FOLLOWS THE PATTERN

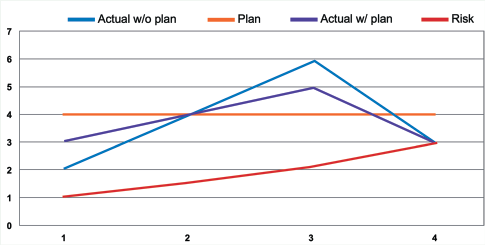

Safety events follow a similar type of evolution (Fig. 3). Work that is executed without the benefit of planning and scheduling tends to have a lot of variability in it, as demonstrated by the blue line. Now, if you ask the managers, the expectations often look like the orange line. Why wouldn’t we expect zero variability on our work if it has been properly planned and scheduled?

In reality, if the unplanned/unscheduled job was executed according to the orange plan, it might look more like the purple line. Notice that there is still some variability, though the work is executed closer to expectations than before. Why does the work not follow the plan exactly? Because the plan is based on a certain set of ideal, 100 percent repeatable conditions.

Realistically, the worker executing the job faces a requirement to adapt to circumstances that don’t always exactly match that perfect plan. We always seek to make sure our plans are as accurate as possible. However, acknowledging that our workers must safely adapt execution of our processes and procedures to the circumstances presented to them is where the most value is gained. This concept is referred to in HOP circles as “employees working the blue line.”

In Figure 3, the red line represents the risk that is inherent in every job that is being performed. Where the red line and the blue line intersect is where injuries occur. Our workers deal with ensuring that the blue line and red line never meet, every day. Identification of, and paying particular attention to, critical steps in the job plan is a great way to focus on keeping the blue and red lines apart.

We will circle back to this situation in Part 2 of this article in the July/August issue of Paper360°.

References:

Pre-Accident Investigations — An Introduction to Organizational Safety, 2012, written by Todd Conklin — excellent reference on Human and Organizational Performance by one of the OGs of HOP.

Paper 360

Paper 360