PAUL LAIL

There are two large process areas that cover the majority of governance activities within a modern pulp and paper company: Administrative (ADM) activities, and the Order-to-Cash (O2C) process. Much of the day-to-day work that occurs in managing a paper company can be placed within one of these two areas.

Included within the ADM area is the pay-to-procure process, which encompasses requisitions, purchase orders, material receipt, raw materials/stores inventory management, and accounts payable. Maintenance activities—because of their relationship with purchasing and the storeroom—are considered part of the ADM processes, as are capital projects, asset management, and HR/payroll. Finance applications, including the general ledger, are part of the ADM area and capture the financial impact of the transactions performed in each of these associated application areas.

The O2C process, meanwhile, supports the customer order fulfilment cycle. This is everything from customer inquiries and pricing through customer order creation, scheduling, production, quality and claims management, work-in-process (WIP) and finished goods inventory (FGI) management, warehousing, shipping, customer invoicing, and the accounts receivable process.

The systems that support these two process areas have grown increasingly sophisticated, complex, and all-encompassing over the past two decades. While in the past a paper company could compete with outdated systems and some manual processes, in today’s world, achieving a high level of automation, productivity, and resultant cost-control is an increasing requirement. Information technology (IT) spending has been viewed in some management circles as a cost to be minimized, without appreciation for the business productivity and cost impacts driven by these systems and their resultant processes. Less appreciated is the impact of well-designed systems and IT strategy on lowering costs, including those in IT.

The days when senior management could afford a limited understanding of a company’s systems and strategy in supporting the ADM and O2C processes are rapidly disappearing. Understanding these processes and the systems that support them are an increasing requirement and priority; understanding how the ADM and O2C processes compare provides a foundation for strategy development.

ADM AND O2C PROCESS COMPARISON

At first glance, there are some obvious similarities between the ADM and O2C processes. After all, they both manage orders (one a purchase order, the other a customer order), include inventory management (one for storeroom items and raw materials, the other for WIP and finished goods), deal with invoices (from supplier, to customer), and involve fund transfer associated with invoices (payment to supplier, payment from customer). Taken at face value and at a high level, these similarities seem obvious and a reason to consider both processes in the same light.

Yet upon closer examination, these two processes are quite different—and their differences become important in management of the processes. Our view of these two processes, and their similarities and differences, shapes company strategy in managing and supporting the systems for each process. The following paragraphs explore some differences between the ADM and O2C processes and the impact on IT strategy.

DATA VOLUME VS TRANSACTIONS

One of the starkest contrasts between the ADM and O2C processes involves the volume of data managed compared to the number of transactions on this data. The ADM process involves management of large quantities of data, but the number of transactions relative to the data volume is low. A typical company will manage tens of thousands of different materials to support mill operation. But each particular material may only infrequently be purchased, issued, or used. For instance, a specific type of valve may be ordered and replaced once every two years.

Even the large volume of raw materials that flow through the production process may involve relatively few transactions, with large quantities. In maintenance activities, the functional locations, equipment, bills of material, and maintenance plans required to support these functions are likely numbered in the tens of thousands for a typical mill. Much of this data will be referenced on an infrequent basis—for instance, when routine maintenance plans dictate, outages occur, or a capital job entails a modification or replacement. When working with the ADM process, the skills and standards needed to work with and manage these large data sets are critical. Microsoft Excel is a commonly-used tool in data extraction, management, and reporting with these large data volumes.

In contrast, the O2C process involves more limited amounts of “active” data compared to the ADM processes, but the number of transactions on this data is much higher. For instance, the typical customer order may be referenced and modified hundreds or even thousands of times as the order is scheduled, manufactured or picked, and inventory is staged and shipped.

The number of orders or inventory items active at any one time may be relatively small, with most data in order or inventory files referencing past history that is kept for archive purposes. While certain O2C data files may be quite large, the number of items referenced during any one time period will therefore be much smaller. The differences in volume of data relative to number of transactions also shapes other dynamics between the ADM and O2C processes.

TRANSACTION RESPONSE TIME

Transactional response time is an important factor in the O2C process, given the volume of repetitive and time-sensitive transactions. One can surmise that, as the volume and frequency of transactions increase, users become much more sensitive to system response time.

System interfaces on the manufacturing floor also have a time-critical nature. What the O2C process lacks in large data stores it makes up for in the number and time-sensitive nature of transactions on data. While response time is still a factor in the ADM processes, users are more sensitive to the amount of time searching for relevant data among large data volumes, and less sensitive to the amount of time spent on executing transactions on that data.

The time spent in searching for the right part number, for instance, can dwarf by many times the time spent in executing the needed transaction on that part number once found. System capabilities for searching through voluminous amounts of data to find the needed elements, along with the potential to change many records in a single transaction, are more important for ADM process users.

SYSTEM DOWNTIME

There are differences between the ADM and O2C processes in their tolerance to system downtime, whether planned or unplanned. Certain aspects of the O2C process, especially those related to manufacturing flow, converting, and shipping, can tolerate only limited system downtime. Such system downtime in the O2C process can quickly impact manufacturing flow and throughput of equipment.

The ADM areas are not as sensitive to system downtime, with most transactions amenable to manual recording for entry/processing once the system is operational. For instance, storeroom parts can be issued, with the part numbers and quantities used manually recorded and entered when the system is back online. Or, critical purchases can be called in to suppliers and followed up later with the necessary purchasing paperwork. Entry of transactions in the ADM process become more sensitive to downtime during month-end processes than they are at other times during the month.

GENERAL LEDGER IMPACTS

There are also differences in the financial impact of transactions between the ADM and O2C processes. Many types of transactions in the ADM area have financial impacts that must be recorded, because many of these activities impact spending. There is a tight link between these ADM activities and a company’s general ledger. Material receipts, stores issues, and payment of invoices all have a financial component that must be accounted for and properly recorded. Maintenance work order spending, whether for materials or services, must be captured and capitalized or expensed. Because of the need to audit financial transactions and maintain tight controls on authorizations, users involved in the ADM process typically have individual accounts with approval required over which transactions can be accessed.

Conversely, the nature of most transactions in the O2C process are different in that the impact on a company’s financials are not as direct, although there are exceptions such as customer invoicing, freight management, and claims. But the bulk of transactions related to customer orders do not generate financial entries because there is no direct tie to spending. On the production floor, it is common for generic accounts to be used instead of individual user accounts, given the time-sensitive nature of transactions, the use of terminals by station, and lack of direct spending commitments.

EXTERNAL STAKEHOLDER DIFFERENCES

Differences between external stakeholders also drive requirements in the ADM and O2C processes. Because the primary external interface in the ADM process is with suppliers, a company has more latitude in terms of how it chooses to transact and capabilities it offers to these suppliers. Suppliers will adapt to a company’s way of doing business, understanding limitations or differences as a cost of doing business.

However, it’s a different situation when dealing with customers, which are the primary external interface with the O2C process. Customers can often dictate what they expect in terms of how the supplier transacts or provides data to them, and changes in these requirements can set off urgent work to address such changes. A company must choose how responsive to be in addressing customer requirements, and typically has less latitude here than in requests from suppliers. Customer demands can therefore cause changes in the O2C process and dictate the need for design flexibility in external-facing data transfers and documents.

PROCESS DIFFERENCES

AND IT STRATEGY

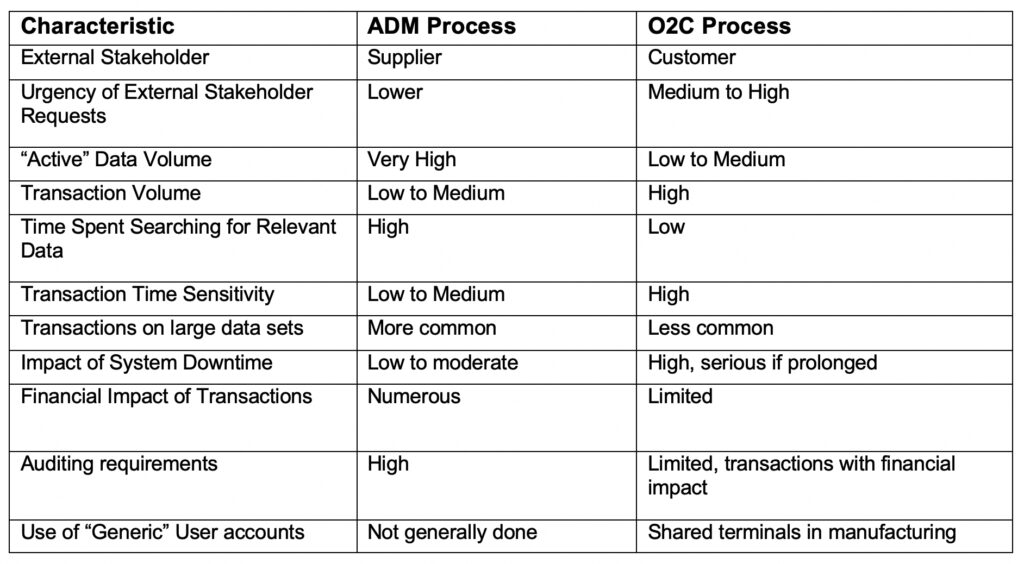

Table 1 summarizes the differences between the ADM and O2C processes that have been noted. The trend for many companies and industries over the past 20 years has been to implement Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) software that encompasses both the ADM and O2C process areas. However, there are three factors that have frustrated many pulp and paper companies in this approach.

The first factor relates to the differences discussed so far between the nature of the ADM and O2C processes in the pulp and paper setting, which drives different process and system requirements. The second factor relates to difficulties handling certain aspects of the O2C process in ERP software, including product attributes and production floor and converting operations. The third factor concerns the area of inventory accounting.

INVENTORY ACCOUNTING OPTIONS

How a company financially accounts for inventory transactions across the various categories of inventory is an important element of process and system design. This also has large implications for how the ADM and O2C processes relate to one another.

Within the ADM process, transactions for storeroom inventory are straightforward, given the discrete nature of storeroom inventory transactions and the embedded nature of storeroom inventory in the ADM process. Here it makes sense to record the financial impact of storeroom receipts and issues as they occur.

When it comes to non-storeroom inventory transactions, however, there is a choice to be made on financial recording and valuation. These non-storeroom inventory transactions include those for raw materials, WIP, and FGI. An organization must decide how important it is to record the financial impact of inventory transactions in these areas as they occur, versus in a batch manner at the end of an accounting period. Note the financial impact of inventory transactions is a separate matter from maintaining the current units or quantities of inventory items. How financial accounting is performed for non-storeroom inventory is the single most important question affecting design of how the ADM and O2C processes relate to each other for pulp and paper mills.

In discrete manufacturing, components in the bill of material are assembled in the manufacturing process into an end product that is then sold to customers. Because of the discrete nature of the process, it is easier to determine the number of parts used and to account for these parts during the production process.

The characteristics of pulp and paper manufacturing, representing continuous process manufacture, make accounting for in-process production much more difficult. Pulp and paper companies may find financially accounting for each raw material, WIP, and FGI inventory transaction as they occur overly complex and cumbersome. For this reason, determining inventory valuation through a month-end data pull of physical inventory is a common approach that many companies select.

BACK TO IT STRATEGY

In situations when ERP software can cover the entire needs of the O2C process without significant modifications, selecting ERP software to handle both the ADM and O2C processes is the right strategy. When all functions are in a single system, the financial accounting for non-storeroom inventory on a transaction-by-transaction basis is normally inherent within the software design.

For companies in the pulp and paper sector, the ability of capable ERP software to handle applications in the ADM process is fairly certain, with maintenance applications the area of most frequent concern. This is because pulp and paper company ADM processes are quite similar to ADM processes in many other industries. When matching ERP system capabilities to the needs of the O2C process in pulp and paper companies, challenges often arise, given the factors noted of ADM vs O2C process differences, difficulty handling all O2C applications, and frequently a minimal inventory accounting approach.

When ERP software cannot cover the complete needs of the O2C process, two systems will be necessary. If this is the case, the company must choose how the ADM and O2C processes will relate to each other. It is usually much easier to implement one system each for the ADM and O2C process areas, especially if non-storeroom inventory can be valued at month-end, rather than to split the O2C process within itself.

Paul Lail is director, integrated business management, for Verso Corporation, a leading North American producer of graphic and specialty papers, packaging, and pulp. Reach him at [email protected].

Paper 360

Paper 360